Due to the weathering of volcanic rocks and the accumulation of mercury in ancient sediments, mined coal subsequently contains mercury.

Although small quantities of mercury may be emitted while coal is stored and handled, most mercury is released from the combustion stack after it is burned. The boilers operate at temperatures of 1100 ̊C and the mercury in the coal is vaporized and released as a gas. Some of the released mercury may cool down and condense as it passes through the boiler and the air pollution control devices. The amount of mercury in coal that is not emitted into the atmosphere during combustion is trapped in wastes such as bottom ash and recoverable fly ash.

Coal burning, and to a lesser extent the use of other fossil fuels, is one of the most significant anthropogenic source of mercury emissions to the atmosphere. Coal does not contain high concentrations of mercury, but the combination of the large volume of coal burned and the fact that a significant portion of the mercury present in coal is emitted to the atmosphere yield large overall emissions from this sector. The mercury content of coal varies widely, introducing a high degree of uncertainty in estimating mercury emissions from coal burning. Data on mercury content is now available from many countries, including major emitters of mercury.

The updated inventory of emissions to air confirms coal burning as a continuing major source of emissions, responsible for some 475 tonnes of mercury emissions to air annually, compared with around 10 tonnes from combustion of other fossil fuels. According to the new inventory, more than 85% of these emissions are from coal burning in power generation and industrial uses. (GMA 2013).

Mercury emissions from Fossil fuel combustion for power and heating, amount to 45.6% of the Global Mercury Emissions and are the largest anthropogenic source of emissions globally.

Up to 95% of mercury releases from power plants can be reduced. This can be achieved by taking direct measures to reduce mercury emissions, by optimizing control systems for other pollutants, improving coal treatment and improving plant performance.

Relevant legislation and NGO policy work

Globally

The Minamata Convention on Mercury, Article 8 concerns controlling and where feasible, reducing emissions of mercury and mercury compounds, to the atmosphere though measures to control emissions from certain point sources (Annex D) including coal fired powered plants and coal fired industrial boilers. Different measures are requested for existing and new installations.

Furthermore Guidance on Best Available Techniques and Best environmental practices in relation to emissions from point sources under Annex D of the Minamata conventionhas been finalised at UNEP level and should be considered.

Important work is also being carried out under the UNEP Global Mercury Partnership on Mercury Control from Coal combustion. Further relevant documents have been developed under these initiatives.

The ZMWG has been following this issue closely and has been giving respective feedback at the global mercury negotiations. See also the ZMWG fact sheet on Mercury Air Emissions and Continuous Emissions monitoring Systems (CEMS) (Jan 2011).

In earlier years, ZMWG has supported relevant projects to assist the work on emissions, by funding NGOs in countries of focus- Toxics Link (India), EcoAccord (Russia) and with the input from GVB (China).

In the EU

The EU adopted the Large Combustion Plants Directive (LCP), which entered into force in 2001. The overall aim of the LCP Directive is to reduce emissions of acidifying pollutants, particles, and ozone precursors. Control of emissions from large combustion plants - those whose rated thermal input is equal to or greater than 50 MW - plays an important role in the Union's efforts to combat acidification, eutrophication and ground-level ozone as part of the overall strategy to reduce air pollution. The directive mainly addresses and sets emission limit values for NOx, SO2, and particulate matter. Through these measures, mercury releases are also expected to be reduced.

Furthermore, the Directive on industrial emissions 2010/75/EU (IED) has been adopted on 24 November 2010 and published in the Official Journal on 17 December 2010. It has entered into force on 6 January 2011 and was transposed into national legislation by Member States by 7 January 2013.

The LCP directive has been incorporated into the IED. Technical provisions and emission limit values for NOx, SO2 and dust related to coal combustion are in annex V of the IED.

IED sets out the main principles for the permitting and control of installations based on an integrated approach and the application of best available techniques (BAT) which are the most effective techniques to achieve a high level of environmental protection, taking into account the costs and benefits. For more information on the directive please visit the EC website.

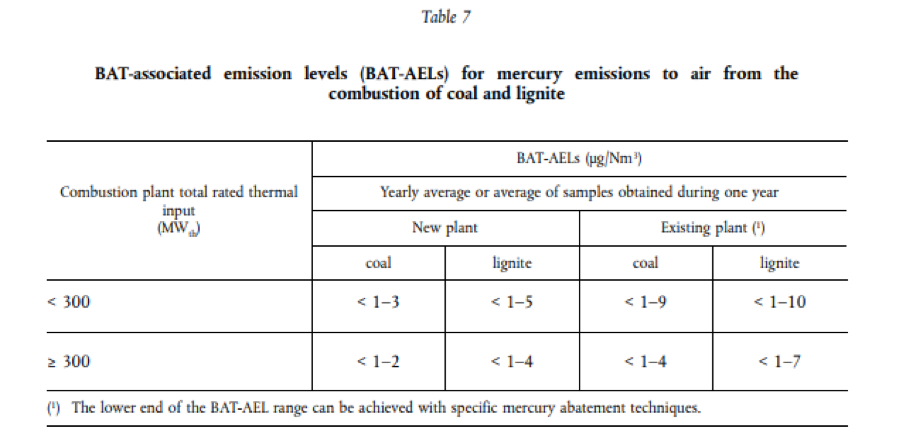

The benchmarks or criteria on which BAT relies are described in the BAT Reference Documents (BREFs). The first Large Combustion Plant BREF was published in 2006. The BREF was revised in 2017 and BAT Conclusions were also adopted on 31 July 2017.

Through the implementation of the IED, the role of the BREFs has been strengthened. After a BREF is completed, it should be subject to BAT conclusions that are adopted through a comitology decision (implementing act). The right of initiative however rests with the Commission. BAT conclusions contain parts of the BREF, their description, information on applicability, including BAT Associated Emission Levels (BATAELs) for different pollutants (meaning emission levels that can be achieved for a pollutant if the industry is implementing BAT) as well as associated consumption levels and monitoring. It may also include site remediation measures “where appropriate”.

Within 4 years after publication of the comitology decision on the relevant BAT conclusions, local authorities should review and update all the permits to the respective industries in order to make sure the industrial activity operates according to the requirements set out in the BAT conclusions.

The provision in the IED requires that Emission Limit Values (ELVs) for pollutants set out in the permit should not exceed the relevant BATAEL. However the permit writer may derogate in specific cases and set higher ELVs under certain conditions. An assessment needs to demonstrate that the application of the BATAEL would lead to disproportionate higher costs compared to the benefits due to the local conditions (technical characteristics of the plants, or geographical location or local environmental conditions). In any case no significant pollution may be caused and a high level of protection of the environment as a whole is achieved. Environmental Quality Standards also need to be respected. These derogations are subject to public participation and scrutiny by the public concerned, which includes NGOs.

BAT conclusions include mercury related provisions